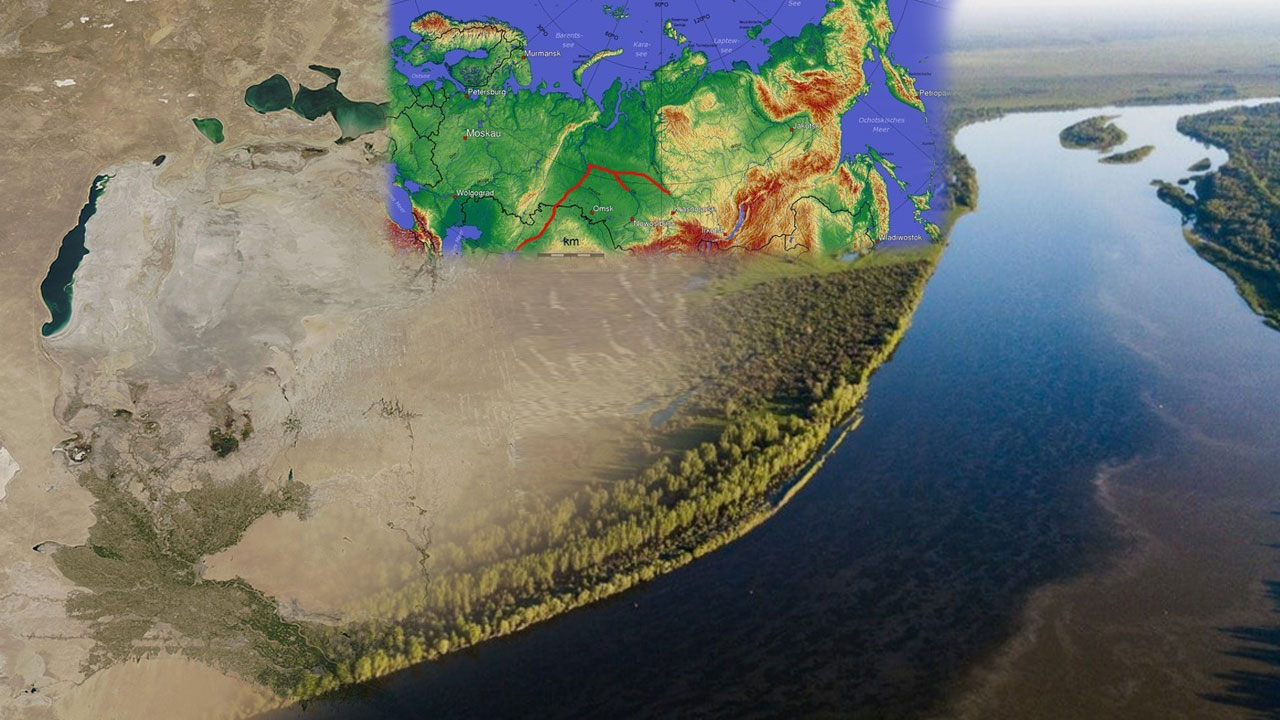

Reviving the mega-canal: Could Siberian water save the Aral Sea?

The Russian Academy of Sciences has announced that it is studying the possibility of redirecting part of the Ob River’s water to Central Asia, including Uzbekistan. How realistic is the idea of bringing water from Russia to the Aral Sea? Is it actually feasible?

The most pressing and acute issue on the agenda of Central Asian countries is water scarcity. Natural population growth, rising water consumption, anomalously hot weather becoming the new norm due to climate change, fewer snowy days, and irrational use of water resources are all deepening the problem. In this context, any proposal or idea aimed at improving the situation is taken seriously and thoroughly examined by both experts and the region’s population. In particular, it has been reported that the Russian Academy of Sciences is exploring the feasibility of implementing a project to divert part of the Ob River’s flow to Central Asia, including Uzbekistan. How well does the idea of bringing water from Siberian rivers to the Aral Sea correspond to current realities? Is it doable? That is what we will discuss today.

Origins of the project

The concept of building a canal from Russian rivers to the Aral Sea did not emerge yesterday or today. As early as 1868, Kyiv University graduate Yakov Demchenko developed a plan to redirect water from the Ob and Irtysh rivers into the Aral–Caspian lowland. At the time, the idea was shelved because there was no perceived need for it. After a long pause, in 1948 academician Vladimir Obruchev wrote to Stalin about the possibility of “feeding” arid Central Asia with Siberian water. The “father of nations” ignored the proposal.

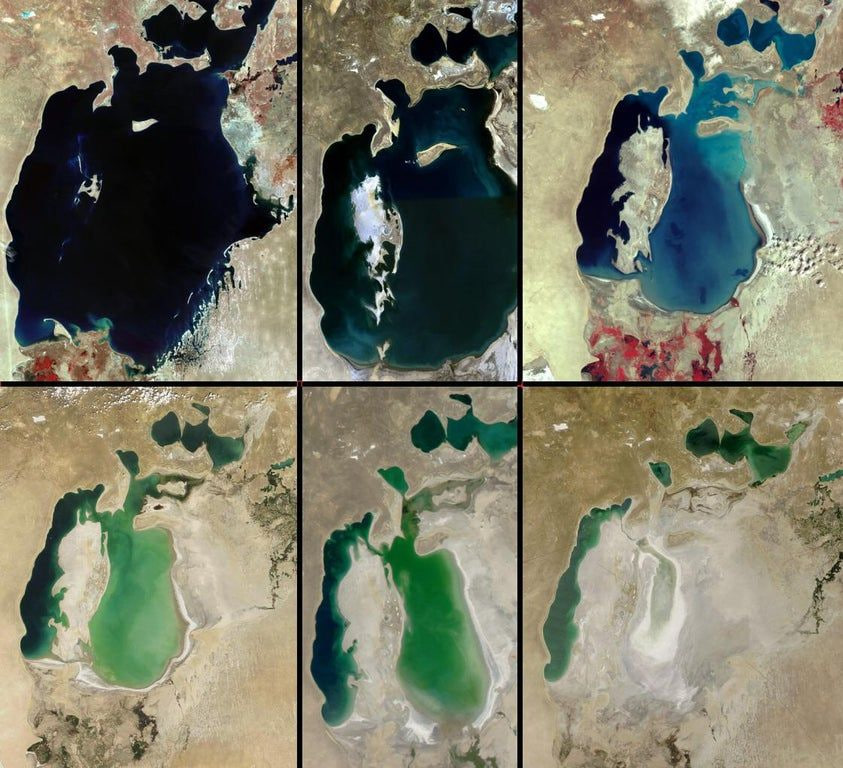

One of the project’s most ardent supporters was Shafik Shokin, president of the Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences. He warned that unless northern rivers were turned southward, the Aral Sea would soon dry up completely, desert winds would lift thousands of tonnes of salt from its bed into the air, and hundreds of kilometers of surrounding land would become uninhabitable.

Real justification for diverting Siberian rivers southward appeared in the 1960s: Central Asia’s natural resources were being depleted while the demand for cotton continued to grow year after year. The waters of the once-mighty Syr Darya and Amu Darya barely reached the Aral, and the sea was visibly turning into a giant saline puddle before everyone’s eyes. If the project had succeeded, vast areas in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan could have been reclaimed and used for agriculture.

The Soviet “mega-project”

In 1968, at a meeting of the CPSU Central Committee, Leonid Brezhnev personally instructed Gosplan, the USSR Academy of Sciences and other organizations to develop a detailed plan for redistributing water from the Irtysh, Ob and Tobol rivers. The use of nuclear explosives was not ruled out to accelerate canal and reservoir construction. By then it had become clear that the Caspian Sea level was also falling rapidly, causing serious concern even in Moscow itself. A powerful new argument emerged when a 458 km canal was built in record time from the Irtysh to the Karaganda region of Kazakhstan. The speed of completion inspired the project’s proponents. Plans were drawn up to extend this same canal to carry Siberian river water all the way to the Caspian and Aral seas.

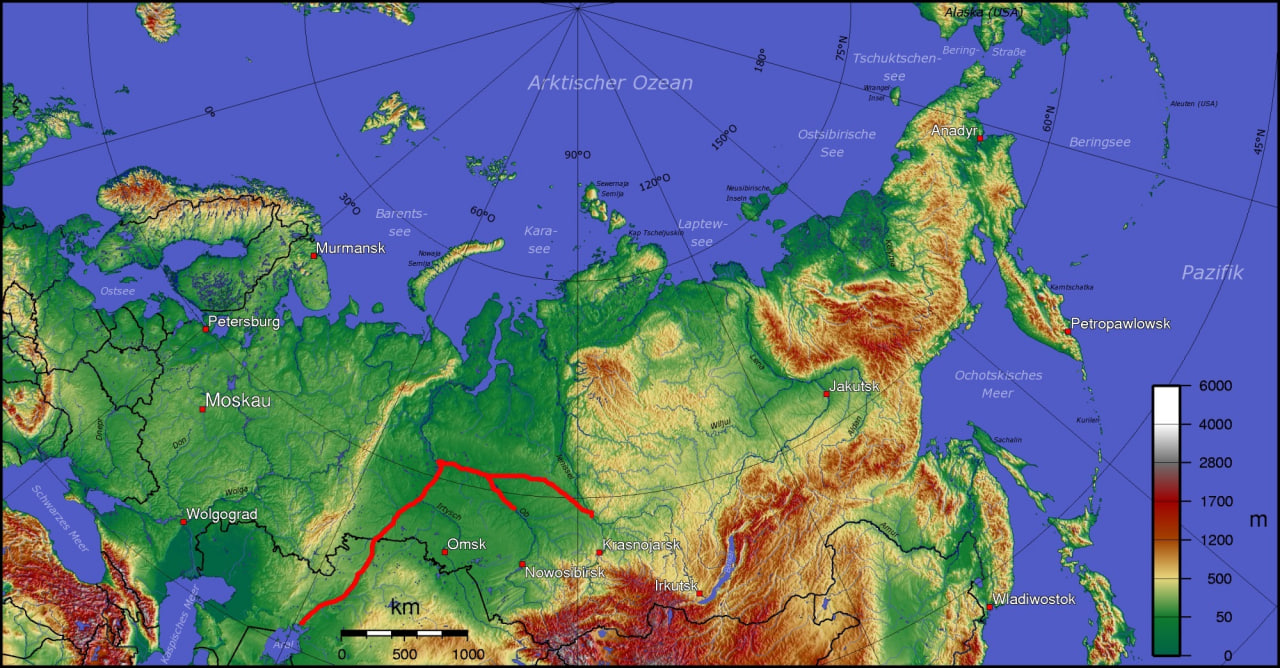

By 1976, technical documentation for diverting the Siberian rivers was ready. Scientists proposed four routes – two northern and two southern. The “southern route” envisaged digging a single main canal 2,500 km long from the Ob–Irtysh confluence to the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. Authors of the “northern route” recommended a shorter canal from the Ob in the Khanty-Mansiysk area to the Irtysh basin and then to the Tobol, after which water would flow through the Turgay Depression – linking the West Siberian Plain with the northern Aral region – and be pumped into a large canal feeding the Amu Darya and Syr Darya.

Because it was relatively cheaper, the “northern route” was approved for the initial phase. A special commission was established with participation from the USSR Academy of Sciences, Gosplan, Gosstroy, the Ministry of Water Resources and a state committee under the Council of Ministers. Work began.

Cancellation of the project

More than 160 organizations across the USSR worked on the project for over twenty years. The resulting materials filled 50 volumes, with drawings and maps comprising more than 10 albums. At the time, the project was estimated to cost 32.8 billion rubles – a huge sum even for a superpower like the Soviet Union.

From the moment the issue was first raised and planning began, there had always been strong opposition. The rigid political system of the USSR allowed no room for dissent. Only after Gorbachev came to power and politics began to liberalize did large numbers of people openly oppose Moscow’s plans. Angry articles appeared one after another in the press. In 1986, the diversion of Siberian rivers became a regular topic in numerous literary publications.

Against the backdrop of enormous expenditure on the war in Afghanistan, lack of funding for such a gigantic project, and widespread opposition from scientists, writers and other intellectuals, on 14 August 1986 the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee officially halted the project to redirect Siberian river water to Central Asia.

The situation today

After the collapse of the USSR, the government of Kazakhstan held talks with Russia about implementing the once-abandoned project on its territory, but without positive results. The Kremlin has no desire to “give away” its internal resources. The Siberian rivers are regarded as a strategic asset of Russia. Water may become a geopolitical resource comparable to oil in the future, so Moscow prefers to keep it under its own control.

Furthermore, changing the flow of the Siberian rivers is cited as likely to disrupt the ecological balance in the Arctic region, affect Siberia’s forest zones, and increase salinity in the lower reaches of the Ob where it enters the Arctic Ocean. According to calculations by Dmitry Sozonov, an expert at IES Engineering & Consulting, the cost of a project to bring water to the Aral Sea today would be at least $100 billion.

In conclusion, diverting the flow of Siberian rivers to Central Asia is technically feasible. It could be achieved with giant pumping stations, long pipelines and modern water-lifting mechanisms. Yet from an ecological, financial and political perspective – it is almost impossible. For Central Asia, the only correct and realistic path forward remains efficient management of existing water resources, introduction of water-saving technologies and strengthened regional cooperation.

Related News

16:26 / 11.12.2025

Drone attacks disrupt flights between Uzbekistan and Russia

19:17 / 10.12.2025

“They tricked me into signing” – Uzbek migrant worker recounts forced recruitment into Russian military

17:11 / 09.12.2025

Uzbekistan and Russia agree on flexible pricing for international train services

13:08 / 04.12.2025