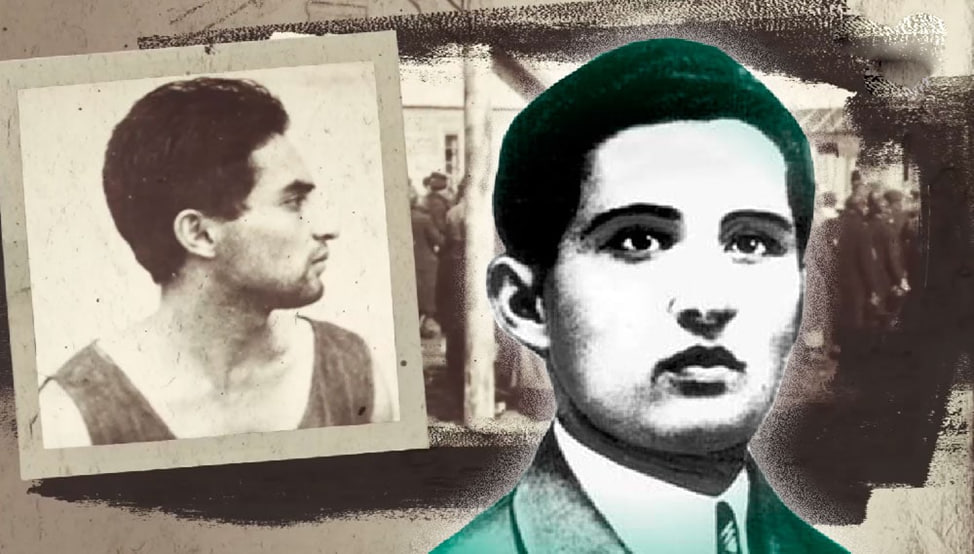

A poet silenced by Stalin’s terror – the tragic fate of Usmon Nosir

Usmon Nosir emerged in the 1930s like a lightning bolt on the horizon of Uzbek literature, one of its brightest figures. His life is a story of talent, rebellion, and tragedy. Though his life was short, he breathed new life into Uzbek poetry, and his works continue to stir readers today. Born in Namangan, raised in Kokand, educated in Moscow, and dying in a Siberian labor camp – Usmon Nosir's life is not just a literary legacy, but a symbolic reflection of the victims of a repressive regime.

Usmon Nosir was born on November 13, 1912, in the city of Namangan into a poor artisan family. Orphaned of his father at age four, he was initially raised by his uncle. After his mother, Kholambibi, married a man named Nosirhoji, the family moved to Kokand in 1921. Recognizing Usmon’s talent, Nosirhoji taught him the Arabic script and enrolled him in a Russo-native boarding school. There, Usmon was introduced to the best of Russian and world literature, especially the poetry of Pushkin and Lermontov, which left a deep impression on him.

Nosirhoji supported Usmon’s love for literature, but the family’s financial difficulties meant that young Usmon often had to work while studying. During his school years, he worked at the Kokand Theater as a literary assistant.

Usmon studied at the “Yangi Hayot” (New Life) and second stage schools in Kokand and in 1929 gained admission to the scriptwriting faculty of the Cinematography Institute in Moscow. However, due to financial hardship, he had to return to Kokand a year later. During this time, he worked as a teacher, literary advisor at the theater, and head of short-term courses. His youth coincided with the emergence of new movements in Uzbek literature, particularly proletarian poetry, which shaped his creative path.

Usmon Nosir’s poetic journey began in 1927. His first poem, “Haqiqat qalami” (The Pencil of Truth), was published that year in the newspaper “Yangi yo‘l”. By the early 1930s, he had already made a name for himself as a poet with a distinctive voice in Uzbek literature. His poems such as “Tojikhon”, “Monologue”, “Heart”, and “The Nile and Rome” became cornerstones of Uzbek literature and played a vital role in shaping the image of the hero of a new historical era. Usmon Nosir aimed to express significant life events through the emotions of a lyrical hero, setting his work apart from that of his contemporaries.

His epic poem “Naxshon” showcased not only his lyrical talent but also his mastery of epic poetry. It is regarded as a major achievement in Uzbek literature. His plays such as “Victory” (1929), “Nazirjon Khalilov” (1930), “The Enemy” (1931), and “The Last Day” (1932) were successfully staged in the Kokand Theater, marking his early successes in dramaturgy.

In 1932, his poetry collection “Quyosh bilan suhbat” (Conversation with the Sun) was published, followed by “Safarbar satrlar” (Mobilized Verses) and “Traktorobod”. His 1935 collection “Heart” and 1936’s “My Love” earned him wide acclaim. His poems captivated readers with their rawness, rebellious spirit, and profound meaning conveyed in simple language. Prominent poet Turob Tola once wrote:

“He stormed in with such a wave and uproar that many poetic styles were swept aside. We called him ‘Uzbekistan’s Lermontov.’ Moscow newspapers wrote, ‘Pushkin has emerged in the East.’”

Usmon Nosir was not only a poet but also a skilled translator who significantly enriched Uzbek literature. His translations of Pushkin’s “The Fountain of Bakhchisarai” and Lermontov’s “The Demon” brought Russian classics to Uzbek readers. These works served as an important bridge between world and Uzbek literature. His love for Heinrich Heine and Mikhail Lermontov is clearly reflected in his sonnet ‘Again to My Poem’:

“I befriended Heine, sought help from Lermontov.”

Usmon Nosir’s translations were rich in both literary and philosophical meaning. He introduced the rebellious and romantic spirit of world literature into Uzbek poetry, playing a vital role in shaping new literary currents in Uzbekistan.

At the peak of his creative career, on January 27, 1937, the tenth anniversary of Usmon Nosir’s literary activity was celebrated on a grand scale. Yet just six months later, his “behavior” was discussed at the Writers’ Union. On July 13, 1937, he was arrested and labeled an “enemy of the people.” His books, manuscripts, and photographs were confiscated. He was initially held in Tashkent Prison before being exiled to prison camps in Zlatoust, Vladivostok, Magadan, and finally the Mariinsk camp in Kemerovo region.

After his arrest, Usmon wrote to his sister Rohatoy from Tashkent Prison:

“Dear sister, Rohatkhan! Go to Uygun’s place and collect my belongings. My coat is at Madamin Davron’s house. My boots are at Ibrohim Nazir’s. Bring them and send them in to me. Looks like I’m about to leave…”

This letter would be one of his last communications with his family.

In 1940, from the Magadan prison, he wrote a letter to Joseph Stalin requesting a review of his case. He stated that he was still writing in prison and had completed a “poetic novel” and three plays:

“I am still young and full of energy. I must create for the people! I am not guilty!”

The letter went unanswered. In 1943, he was transferred to a camp near the village of Suslovo in Kemerovo, and on March 9, 1944 – just after turning 32 – he died of exhaustion and harsh conditions. His burial site remains unknown, though fellow inmates built a symbolic grave in his memory.

The tragedy of Usmon Nosir’s fate did not erase his literary legacy. In 1957, the Supreme Court of the USSR posthumously acquitted him. His works began to be republished, though many of his manuscripts were lost. In 2022, under a decree from President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Usmon Nosir’s 110th anniversary was widely commemorated. A statue of the poet was erected in Namangan, and streets in both Tashkent and Namangan were named after him.

When his niece Nodira Rashidova visited the Mariinsk camp in Kemerovo, a local librarian tearfully recounted how Usmon continued to write poetry even in prison.

His poem “Forget Me Not, My Garden” became a symbol of his eternal legacy. In it, he envisions his verses as immortal memorials that will resonate “even a thousand years from now.” Today, Usmon Nosir is remembered not only in Uzbekistan, but also in the remote Russian villages where he spent his final days.

Usmon Nosir’s life and work are among the most significant pages in Uzbek literature. His poems celebrated patriotism, freedom, and love, even as the totalitarian regime tried to silence his voice. Yet his works left an indelible mark on the hearts of his people. His tragic fate is a lasting reminder of the value of justice and the necessity of freedom.

Doniyor Tukhsinov