Freedom of expression remains fragile in Uzbekistan, but a limited recent opening may be impossible to reverse – The Diplomat

Despite some improvements in ensuring freedom of expression, Uzbekistan is lagging behind in international freedom of speech rankings. The Diplomat, an international current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific region, focused on reasons pulling the country down in such rankings and provided cases where the rights of individuals to express their points of view were violated.

“Over the past four years under President Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan has been on a path to reform. He granted more space for citizens to voice their concerns and grievances. Social media platforms, many of which had been blocked, were made available to the surprise and joy of Uzbekistan’s population and were many foreign news sites. New bloggers and websites mushroomed to fill in the gap in the country’s desolated media space. Social media, in particular, has become a public square that allows people to discuss openly the social and political issues of the day,” The Diplomat writes.

“However, four years into Mirziyoyev’s reforms, freedom of speech in Uzbekistan is far from a given. While the president has repeated on numerous occasions that journalists and bloggers should be free to criticize those in power, and improvements have been noted, Uzbekistan continues to languish at the bottom of many freedom of speech rankings,” the article reads.

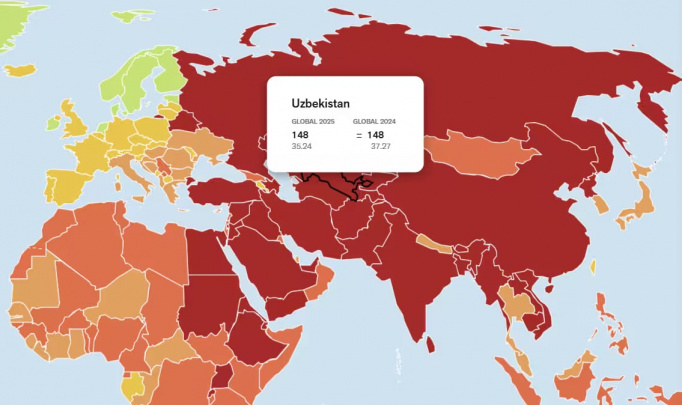

According to the Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom rating, in 2020 Uzbekistan ranked at 156th place in the world (it was 166th in 2016), while Freedom House continues to label the country as “not free,” with a score of 10 out of 100 in 2020 (its score in 2017 was 3 out of 100).

In September, during an online Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) conference marking the International Day for Universal Access to Information, Komil Allamjonov, chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Public Foundation for Support and Development of National Mass Media, commented on the country’s continuously low rankings.

“From 2017 to 2020 it rose by 13 positions. But are there any problems? Of course, there are. Do journalists and bloggers have no fear? Of course, they do, otherwise, the results would have been better. Censorship of certain people, self-censorship of journalists and bloggers, threats or pressure from government officials – naturally, such factors still exist and we are fighting them,” he said.

“These days, at the order of the president, another important document is to be adopted, that is a law aimed at increasing the responsibility for obstructing the activities of the media and putting pressure on journalists. We are waiting for this. We understand that we are still at the beginning of the path and that there will be mistakes and shortcomings along the way,” Allamjonov noted back then.

In the article, The Diplomat counted numerous cases related to violation of freedom of expression in Uzbekistan. In particular, the case with video blogger Shavkat Egamberdiyev who was forced to remove a satirical video that allegedly offended the reputation of Artel and Akfa, companies founded by the khokim of Tashkent, Jakhongir Artykhodjayev, the khokim’s threatening comments to journalists with public embarrassment (“I’ll put you in a gay taxi and in six seconds and you’re done!”) and physical violence (“Leave the house for two or three days without any reason, and you will be gone”) are among them.

“Outside of Tashkent, the situation is even grimmer. In August, the authorities of the autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan summoned a journalist in the middle of the night for reporting on the death of the republic’s chairman, which was officially announced days later. The same month, a blogger from the Uzbek exclave of Sokh was transported to the Fergana region with a hood over his head for calling for the ousting of Fergana’s long-standing khokim, Shukhrat Ganiyev,” the reports reads.

In March, the government introduced new legislative amendments against spreading panic and disseminating false information about the coronavirus, both punishable with up to three years of imprisonment.

In early May, apparently due to construction errors, the Sardoba dam in the Syrdarya region burst. The ensuing flooding displaced 100,000 people in both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Anora Sodykova, a reporter with the state-run Uza.uz news agency, went to investigate the situation, to talk to the affected people. It left her in shock. People who had lost everything in the flood repeatedly expressed thanks to the president for his willingness to compensate them for their losses.

Distraught, Sodykova wrote a post on Facebook expressing her anger over the situation.

“Who are we? What sort of people thank the government before anything has been done? For barely getting bread with butter,” her post read. It soon went viral.

“My editor called me and asked me to remove my post. I said that I would not do that, that people’s reaction was a result of the past twenty years. I have nothing against Mirziyoyev,” Sodykova said.

Several days later, she learned that she had been dismissed.

“I wrote on Facebook that Hayriddin Sultanov (the president’s speechwriter) has fired me. Our relationship was tense from the beginning and only he could influence the decision of my editor. I got reliable information that it was him,” she said. “I gave an interview to the BBC and many people shared my post, even MPs. People supported me, they said that journalists should not be fired for Facebook posts.”

Following her second post, the pressure increased. Some people began to call her introducing themselves as tax office employees and asking about a business she had closed years earlier. Soon after, threats followed. Her husband began receiving phone calls from people threatening him with imprisonment for his alleged support of radical Islamist movements. They made it clear that living under one roof with his wife had become dangerous. Sodykova’s husband could not stand up to the pressure. He left her and took their son with him.

In the end, Sodykova agreed to publicly apologize and she got her job back. But the feeling of injustice did not leave her.

Other methods of pressure are more indirect. As several journalists have told The Diplomat, companies owned by business moguls have been organizing events for journalists and bloggers to influence their reporting with nice treatment and gifts. Others have run old school troll factories out of local universities to violently condemn posts about their bosses’ wrongdoings.

But despite the pressures, some processes are impossible to halt.

“The public used to be afraid to give comments to the media. Now, when they see you with a camera, they are eager to talk. There is still fear among journalists and self-censorship is common, but it will soon be impossible to pressurize media workers because if something happens, people react immediately,” says Darina Solod, a journalist and editor-in-chief of Hook.report.

“Society has changed and no one can control the flow of information. They can try to block Facebook, but people know how to bypass it. They can try to turn back time to the Karimov era – but it will not work,” she noted.

Related News

16:45 / 02.05.2025

Uzbekistan ranks 148th in Press Freedom Index

20:53 / 17.04.2025

National Agency for Prospective Projects files police complaint against economist over criticism of Temu ban

21:32 / 14.05.2024

Saida Mirziyoyeva and Komil Allamjonov meet with U.S. Ambassador, discuss media freedom in Uzbekistan

14:32 / 03.05.2024