Beyond Tashkent: Air quality is a national problem – are policies keeping up?

In recent years, Tashkent has experienced a sharp deterioration in air quality, frequently ranking among the world’s most polluted cities due to elevated levels of PM2.5 particulate matter. Multiple factors, including emissions from heating systems and transport, combined with atmospheric phenomena such as temperature inversions, have exacerbated the problem. The resulting pollution has sparked widespread public concern, placed strain on healthcare services, and prompted a series of government interventions. Yet, questions remain about whether these measures will achieve lasting improvement or if attention will fade once the smog temporarily clears.

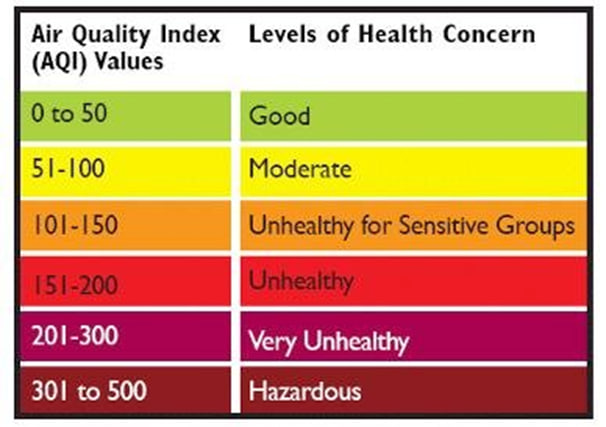

Air quality in Tashkent has fluctuated significantly, with sharp declines observed during October and November. Reports indicate AQI levels ranging from “Good” (8–37) to “Unhealthy,” with certain days placing Tashkent as the world’s second most polluted city—such as November 10, 2025, when PM2.5 concentrations reached 121.6 µg/m³.

The former Ministry of Ecology, Environmental Protection, and Climate Change, reorganized on November 19 into the National Committee on Ecology and Climate Change by presidential decree, has noted that peak pollution typically occurs in late autumn and winter, as well as during major dust storms. A notable example occurred in September 2025, when the Air Quality Index reached a hazardous 556, largely due to dust carried from the Kyzylkum Desert.

Understanding the crisis: Pollutants and their sources

The current air quality crisis represents the culmination of a decade-long deterioration. Data from 2013 to 2023 show a consistent rise in pollutant concentrations across Tashkent, primarily driven by human activity. According to AQI reports, Uzbekistan’s air pollution stems from three main sources: transport, industrial and energy sectors, and environmental disasters.

Vehicular emissions

Transport, particularly the widespread use of vehicles in Tashkent, is a major contributor to air pollution. The problem is intensified by the prevalence of older cars and motorcycles, many of which no longer function efficiently. Due to less stringent emission standards and economic constraints, these vehicles release disproportionately high amounts of smoke, noxious fumes, particulate matter, and unburned fuel or oil vapors, significantly worsening air quality.

Industrial and energy sectors

Industrial activity and energy consumption further contribute to air pollution year-round. Factories, power plants, and other industrial facilities burn large quantities of coal and fuel, consistently emitting harmful pollutants. Additionally, natural gas and mineral extraction operations rely on heavy diesel machinery, which generates fine dust and particulate matter. This activity increases both PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations while releasing hazardous byproducts.

The Aral Sea ecological disaster

In northwestern Uzbekistan, the dried-up seabed of the Aral Sea poses another severe source of pollution. Decades of overuse have left vast salt flats contaminated with pesticides, residual fertilizers, and heavy metals. During windstorms, these toxic salts are carried into the air, creating massive and unpredictable dust events. These storms transport dangerous chemicals, posing serious health risks to populations downwind across Uzbekistan and neighboring regions.

What are PM2.5 and PM10?

Particulate matter (PM) refers to a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets suspended in the air:

- PM10: Inhalable particles with diameters of 10 micrometers or smaller, such as dust and pollen. These particles are typically trapped in the nose, mouth, or throat.

- PM2.5: Fine inhalable particles with diameters of 2.5 micrometers or smaller—about 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair. Due to their minute size, PM2.5 particles can penetrate deep into the respiratory tract and even enter the bloodstream, posing significant health risks.

Why does AQI change so rapidly?

IQAir, a Swiss technology company, serves as a primary source for real-time Air Quality Index (AQI) data that frequently ranks Tashkent among the world’s most polluted cities. The company operates a vast network of 96 monitoring stations, managed by 64 contributors, which continuously collect raw pollutant concentration data (measured in µg/m³). This data, particularly for PM2.5, is processed using a standardized formula to produce the color-coded AQI score.

Rapid fluctuations in AQI are primarily attributed to:

- Meteorological conditions: Temperature inversions and weak winds, particularly in winter, trap pollutants over the city. Tashkent’s location in a mountain-surrounded basin limits natural air circulation.

- Sudden dust storms: Strong westerly winds can lift and transport large volumes of dust from the Kyzylkum Desert and neighboring Kazakhstan, causing sharp spikes in PM2.5 and PM10 levels.

Additional factors and context

Government reports estimate that up to 28% of pollution originates from burning coal and fuel oil in private homes, greenhouses, and power plants. This reliance on coal, intensified by a government initiative to conserve natural gas, significantly increases PM2.5 concentrations.

Vehicular emissions further exacerbate the problem. Uzbekistan’s aging vehicle fleet, combined with the widespread use of low-quality A-80 gasoline, contributes approximately 16% of pollution, or up to 60% of hazardous airborne chemicals. The rapid growth in car ownership, alongside continuous construction and the loss of green spaces, which act as natural air filters, adds to dust levels. Industrial and energy facilities also release pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO₂) and carbon monoxide (CO), compounding the issue.

Beyond Tashkent: A national challenge

Air pollution is not confined to the capital. Cities such as Bukhara, Samarkand, Urgench, Termez, and Nukus regularly experience high dust levels, while Nurafshan and Fergana face elevated nitrogen dioxide concentrations, indicating widespread air quality challenges across Uzbekistan.

- Fergana: Pollution levels have occasionally reached public health emergency levels, with AQI peaking at an unprecedented 1,093 at 8 p.m. This “extremely hazardous” level poses immediate risks to the entire population, decreasing only slightly to 963 by 9 p.m.

- Termez (Surkhandarya): Residents frequently experience a strong, hot, dust-laden wind from northern Afghanistan. Blowing at 15–20 m/s, it triggers prolonged dust storms that can last up to 70 days annually, reducing visibility, harming health, and eroding farmland. This condition is driven by cold air funneled through mountain gaps in the Bactrian Plain and remains the primary cause of extreme dust events in the region.

- Urgench: Air quality here is heavily influenced by proximity to the dried-up Aral Sea bed, which generates recurrent, toxic dust storms carrying high levels of particulate matter and hazardous chemicals. This natural source combines with urban emissions from traffic, low-quality fuel combustion, and industrial activity, creating a dual pollution challenge for the city.

Impacts and policy gaps

The health consequences are severe. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) project, air pollution accounts for nearly 15% of all deaths in Uzbekistan, with Tashkent among the most affected regions. High PM2.5 concentrations are strongly linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

Despite official pledges to reduce vehicle numbers and improve public transport, residents and activists report that these promises have largely gone unfulfilled, as vehicle numbers continue to rise, undermining attempts to curb air pollution.

Measures, economics, and policy

On November 24, 2025, a major presidential decree outlined urgent measures to address Tashkent’s air quality crisis. Key actions included establishing a Special Commission to oversee air quality, banning low-quality A-80 fuel and vehicles manufactured before 2010 that do not meet Euro-4 standards, relocating polluting industrial enterprises outside the city, and requiring construction sites to implement green zones, water sprayers, and monitoring stations. The decree also called for expanding the air quality monitoring network with 347 new stations, developing a “Green Tashkent” master plan, and creating a continuous “Green Corridor” through urban areas.

The public response was immediate. Demand for air purifiers has surged ninefold over the past three years, with customs data showing imports rising from just 2,000 units in 2022 to over 18,500 in the first ten months of 2025. In response, the government eliminated the longstanding 20% customs duty, previously a minimum of $3 per unit, making these devices more accessible to citizens during the smog crisis.

Despite these measures, experts remain critical of the delayed response. They question the logic of taxing essential health goods during a pollution emergency and highlight the economic and social consequences of forcing greenhouse operators to switch from natural gas to coal, which not only worsened smog but also increased healthcare costs. Public frustration is growing, and experts are calling for accountability over policy decisions that allowed environmental conditions to deteriorate so drastically.

International strategies: Lessons in fighting smog

Reducing PM2.5 and mitigating seasonal smog is a global challenge. Cities facing similar pollution sources – industrial emissions, coal heating, and heavy traffic – offer valuable lessons for Tashkent.

- China: The “Blue Sky Defense Battle” demonstrates how aggressive national campaigns can cut pollution. Measures included phasing out coal, restructuring industries, enforcing vehicle emission standards, and promoting electric vehicles, leading to significant PM2.5 reductions.

- Delhi: The Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) relies on real-time data to trigger automatic measures during severe pollution, such as traffic restrictions, vehicle bans, construction halts, and work-from-home directives. Tashkent’s temporary suspension of cargo vehicles reflects an initial step toward such structured, responsive action.

- European cities: Urban planning combined with clean air strategies, such as low-emission zones (London, Paris), investments in cycling and electric transport, and bans on coal heating (Warsaw), demonstrates how non-combustion pollution can be reduced while promoting sustainable mobility.

Protecting citizens and indoor air

With PM2.5 levels frequently exceeding WHO standards by 20–30 times, health experts from Uzhydromet and the Ministry of Health emphasize both personal and environmental protection. Standard medical masks provide limited protection; N95 or FFP2 respirators, properly sealed around the nose and chin, are recommended. Limiting outdoor activity, especially when AQI exceeds 150, and monitoring real-time air quality via AirUz or IQAir is crucial. After dust exposure, saline nasal sprays help clear particles from the upper respiratory tract.

Indoor air protection is equally important. With customs duties removed, HEPA-equipped air purifiers are essential. Citizens should keep windows closed during peak pollution hours (typically 6:00 PM–9:00 AM in winter), use damp cleaning methods to avoid re-suspending dust, and maintain indoor humidity to trap particles and protect respiratory membranes.

Vulnerable populations – children, the elderly, and those with asthma, COPD, or heart disease – should take extra precautions during hazardous AQI events, staying indoors with air purifiers operating and medications readily available.

Towards a sustainable solution

Addressing Uzbekistan’s air crisis requires a unified, intersectoral approach, with energy, urban, and environmental policies aligned. Transparent communication and public access to accurate air quality data are fundamental. Economically, preventing respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses is more sustainable than managing the systemic health impacts on the workforce. True progress depends on climate justice, ensuring social programs protect the most vulnerable in this new environmental reality.

As Avicenna wrote in The Canon of Medicine over a thousand years ago, clean air is the first essential factor for life. Prioritizing the atmosphere today is a return to ancient wisdom: health cannot exist without the purity of the air we breathe.

Related News

17:49 / 03.03.2026

Uzbekistan to reward industrial enterprises for reducing environmental impact

12:10 / 02.03.2026

Tashkent air quality hits unhealthy levels as PM2.5 exceeds safety limits

21:33 / 25.02.2026

President Mirziyoyev reviews plan to expand green areas in Tashkent

12:15 / 23.02.2026