Uzbekistan’s power struggle: Price liberalization, post-socialist legacies, and red flags in the green transition

Year after year, citizens across Uzbekistan face recurring power outages that disrupt daily life, strain household routines, and trigger growing public frustration. Once limited to remote or rural areas, these blackouts have increasingly reached major cities, including the capital, Tashkent, where residents now face frequent shortages during both winter freezes and summer heatwaves.

As complaints mount and pressure on the system intensifies, the question remains: why does the country continue to struggle with such a fundamental utility in the 21st century?

In an interview with Dr. Salim Turdaliev, a PhD economist and a lecturer at Charles University in Prague who also specializes in energy reforms and household welfare in post-Soviet states, several key insights emerged, spanning outdated infrastructure, pricing policy failures, limited market mechanisms, and the need for better public communication and social protection.

Post-soviet energy legacy and structural challenges

“Georgia and Armenia began this transition 15–20 years ago. Uzbekistan is only starting now.”

Uzbekistan inherited not just outdated infrastructure from the Soviet Union but also a centralized policy framework that treats electricity and gas as public goods. This legacy shapes both consumer expectations and government policies to this day.

“The energy market has not been liberalized… We don’t treat energy as a commercial good,” Dr. Turdaliev explains. “The cost of producing a kilowatt hour of electricity is actually higher than the price it is usually sold for… It was heavily subsidized by the government. When this situation occurs, there is chronic underinvestment in the energy infrastructure. There is no private sector, no international companies who will come, invest, build, and sell because it’s simply not profitable.”

He notes that Uzbekistan is “only starting” its transition toward market pricing, while “Armenia and Georgia… actually implemented block tariffs some 15 or 20 years ago.” In those countries, the move to treat electricity as a commercial good, rather than a subsidized public utility, began more than a decade earlier, creating a very different investment climate.

Aging infrastructure and systemic pressure

The country’s energy infrastructure, much of it built in the Soviet era, has failed to keep up with urban expansion, rising demand, and the increased strain of extreme weather events.

Government officials also attribute winter blackouts to fuel shortages, particularly the insufficient supply of natural gas needed for electricity generation.

The researcher points to the broader issue: decades of underinvestment in modernization. Despite a sharp rise in consumption throughout the 2000s and 2010s, especially in cities, there has been little meaningful investment in upgrading the system.

He links this stagnation to the lack of liberalization in the energy market, where heavy subsidies have left little room for private or foreign investment. As a result, the grid remains vulnerable when demand peaks.

Can price liberalization solve the problem?

“Prices should reflect real market costs. Without proper pricing, investments will remain insufficient.”

This is the question that reformers and policymakers continue to debate. Dr. Turdaliev argues that the price liberalization could be the factor, if not the main one, to address systemic issues with electricity outages.

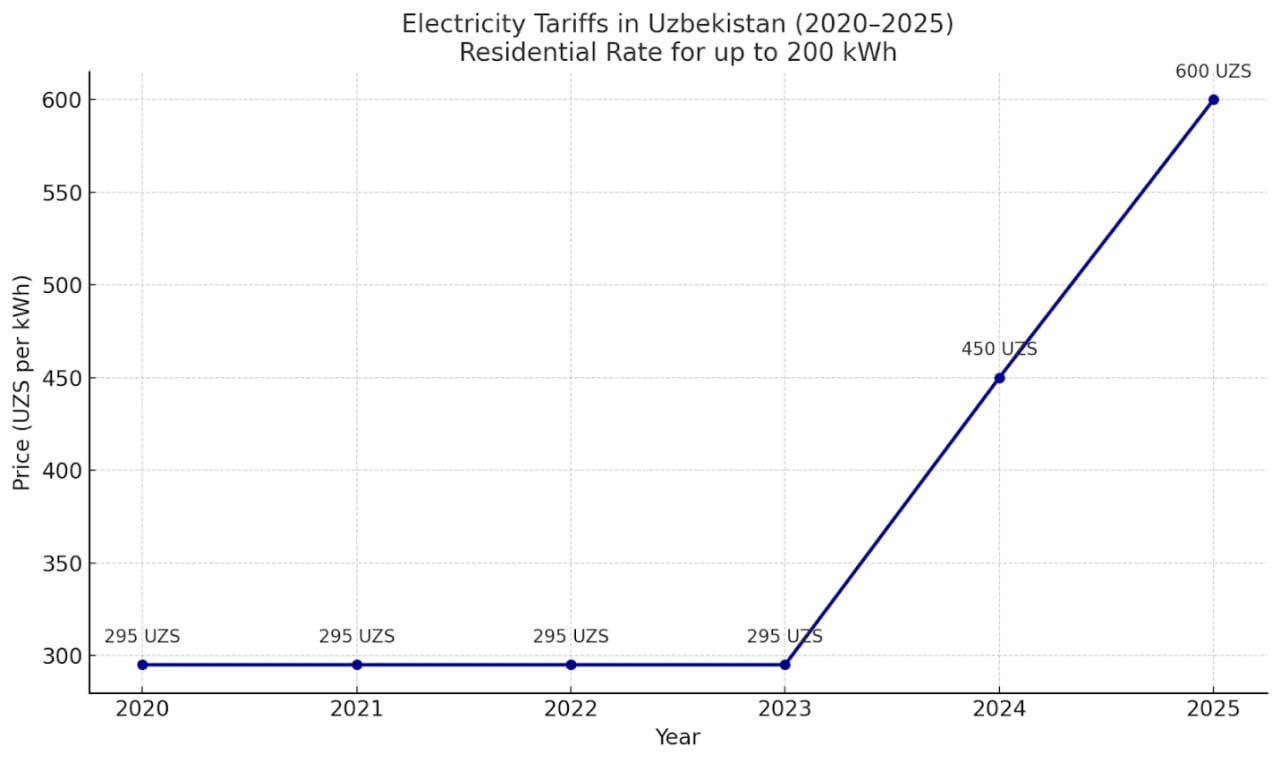

For decades, electricity prices were frozen at UZS 295 per kWh, unchanged from 2020 to 2023. In 2024, the government introduced a “social norm” model, pricing the first 200 kWh at UZS 450. By mid-2025, Uzbekistan had expanded the system:

- Up to 200 kWh/month: UZS 600

- 201–500 kWh/month: UZS 800

The introduction of block tariffs and indexation mechanisms marks a gradual shift toward market-based pricing. However, this transition raises concerns over the burden on households, particularly in low-income regions.

“Without social protection, reforms can push vulnerable families to switch to dirtier fuels, as we saw in Russia.”

The researcher stresses the importance of examining similar cases in other countries that transitioned from subsidized to market-based energy systems. “In Georgia and Armenia, reforms brought investment and improved reliability,” he notes, “but without good social protection measures, you always have the risk of the poorest moving to dirtier fuels.” Drawing on his fieldwork in Russia, Dr. Turdaliev recalls, “Some families could not afford to pay for electricity for heating, so they switched to coal or even kerosene… It’s cheaper, but it produces more indoor pollution and more CO₂… and that is a problem for health and for the environment.”

Foreign investment and the green energy push

For the past several years, Uzbekistan has seen a significant influx of foreign capital directed toward its energy sector. Among the most notable is Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power, which has committed over $15 billion to several renewable energy projects. Chinese investment is growing, including the Russian players, such as Rosatom, have also signaled growing interest, particularly in nuclear energy development. This trend underscores Uzbekistan’s official commitment to alternative sources of energy.

While these investments signal a commitment to green energy, analysis suggests that renewables are not a panacea.

The limits of green energy and alternatives

“The problem with green energy is that it’s not stable. And electricity systems need stability.”

Green energy offers long-term promise, but it presents short-term challenges. “Even in Europe, green energy can lead to grid instability due to overproduction and lack of storage.” According to the researcher, electricity prices in Europe fluctuate in real time based on supply and demand. When wind turbines overproduce, and there’s no way to store electricity, grid operators are sometimes forced to pay people to consume energy to avoid overloads, known as negative pricing or self-cannibalization.

Without storage capacity (like large-scale batteries), green energy cannot reliably replace fossil fuels. Even wealthy nations like the U.S. and Canada still depend on fossil sources.

Uzbekistan, with limited solar and wind integration, lacks both the infrastructure and storage solutions to rely fully on renewables.

“In the short to medium term, Uzbekistan will still rely on fossil fuels to meet demand,” Dr. Turdaliev points out.

Taking that into account, the country must carefully navigate the complex implications of this transition to ensure that environmental goals do not overshadow social, technical, or economic realities.

Data, equity, and environmental oversight

Beyond questions of energy supply, it is critically important that environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs) are conducted for all major energy projects, including those labeled as “green.” These assessments must include community compensation mechanisms, as renewable projects can bring unintended side effects, including potential health risks and disruptions to local livelihoods and well-being.

In some cases, land designated for renewable infrastructure, such as large-scale solar or wind farms, is located in remote or sensitive areas. This raises the potential for both positive and negative externalities. Moreover, waste management must be taken seriously: for example, solar panels are notoriously difficult to recycle, and long-term disposal strategies must be in place.

This is where ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) principles come into play. But ensuring that ESG standards are meaningfully implemented, rather than simply checked off to satisfy investors, ultimately falls on the state, which must take responsibility for robust oversight and enforcement.

Does Uzbekistan take ESG seriously? That remains an open question. While ESG-related policies have begun to emerge in recent years, their practical impact is still unclear.

As Salim Turdaliev notes critically, without reliable data, it will be impossible to assess their real impact.

Institutional reform and public communication and the need for protection

“Trust is the currency of transition. But there’s no communication strategy to engage the public.”

Underlying much of the energy crisis is a broader institutional gap, including governance, regulatory quality, and public trust. From time to time, the public hears allegations about corruption and mismanagement in the energy sector. These concerns add to the erosion of confidence in reforms.

Trust, Dr. Turdaliev notes, is the currency of transition, yet Uzbekistan still lacks a communication strategy to engage the public. Beyond price reforms, he argues, non-price mechanisms can be powerful in shaping behavior. In Armenia, his team tested monthly behavioral messages urging households to reduce electricity use during peak demand. These simple interventions had a measurable impact, especially among those with higher education or who relied on electric heating.

The researcher cautions that tariff design is critical. Block tariffs, where higher consumption leads to higher prices, can unintentionally hit low-income households hardest, while those with average or higher incomes are less affected. “This is why data matters,” he stresses, “because it allows us to analyze the distributional impact of any policy.”

While such tariffs can promote equity, they also carry significant risks if poorly designed.

Evidence from Kyrgyzstan highlights the stakes: studies link frequent power outages to higher rates of childhood stunting, with girls disproportionately affected. This shows that energy insecurity is not only an economic issue but also a developmental and gendered one.

The role of academia and international lessons

“We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We can borrow what worked elsewhere and avoid what didn’t.”

“Academics are often seen as non-practical, but many of our studies have direct policy implications.” Dr. Turdaliev calls for stronger dialogue between government and academia, emphasizing that researchers can provide valuable impact assessments, policy simulations, and insight into population-specific outcomes. Uzbekistan can also learn from the policy experiences of other post-Soviet or emerging economies.

To conclude, Uzbekistan stands at a critical juncture in its energy sector. The current trajectory reflects a complex interplay of structural inefficiencies, institutional legacies, and evolving policy frameworks. Energy reform today is not confined to economic restructuring; it increasingly intersects with social equity, environmental sustainability, and governance accountability. Ensuring reliable electricity access across the country will depend on how these overlapping challenges are addressed in practice.

Interview and article

by Aziza Normuradova

Related News

19:32 / 16.02.2026

Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan agree on power plant operating regime

19:52 / 14.02.2026

Uzbekistan’s renewable energy output surges two thirds in early 2026

13:24 / 12.02.2026

Thousands barred from paying for electricity over allegedly unjustified waste collection debts

17:37 / 11.02.2026